All set. The crowd gathers.

The orchestra, stealthily,

Discreetly place themselves.

The elephant grabs its trunk,

The stag its horn.

And sudenly rises

In the silence

For the pleasure of our five senses

The music of Master Saint-Saëns.

This is how French author, actor and humorist Francis Blanche, born in 1921 – the year Saint-Saëns died – introduced the music of The Carnival of the Animals into the poetic, facetious text he wrote to accompany it. Although Saint-Saëns had forbidden any public performance of his work after its premiere during the 1886 Paris Carnaval, his score, subtitled “Grande fantaisie zoologique” (“Great zoological fantasy”), enjoyed the popularity we all know after his death, inspiring a host of musicians and poets.

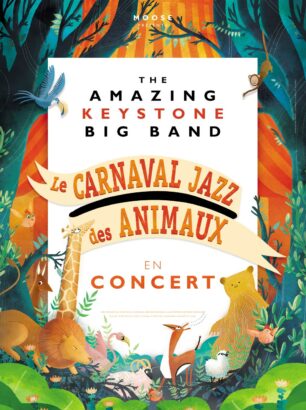

1921 also marked the start of the “Roaring Twenties”, a term referring less to the animal world than to a new type of carnival – that of an exuberant modernity unleashed after the World War I. The years following the death of Saint-Saëns – and the revival of The Carnival of the Animals – were also those of a major musical transformation: people on both sides of the Atlantic began to dance to new rhythms, soon to be grouped under the banner of “jazz” music. This new genre has known many developments over the course of the 20th century, which The Amazing Keystone Big Band sets out to represent in a playful adaptation of Saint-Saëns’ music: welcome to the Jazz Carnival of the Animals.

As if echoing Francis Blanche’s text, who was the first to offer short spoken interludes between the work’s movements to accompany the musical narration, the ensemble comes in as stealthily as a wolf, or should we say as the voice of a wolf, since the narrator here is a large, hungry predator, following the lion’s advice to wander incognito in the middle of the menagerie to choose his prey. Taï-Marc Le Thanh’s tale justifies a reorganization of the various movements in relation to the order of the original work, to better serve a new story full of twists, tricks and setbacks – particularly when it comes to our four-legged narrator crossing the Aquarium River…

Big band obliges, the instrumentarium is of course renewed, but is still designed to characterise each animal or group with specific timbres. The theme of the gallop from Jacques Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld, the famous French cancan, which is slowed to a crawl by cellos and violas in Saint-Saëns’ work to represent the turtles, is found here in the background of a languorous bossa nova, accompanying a tenor saxophone solo. The concert cackling of the barnyard is carried by the trumpets in a funk style at least as effective as Jean-Philippe Rameau’s imitation of the chickens – which Saint-Saëns drew inspiration from –; the elephant-bass becomes elephant-tuba, also offering a most realistic barr; as for the fish in the aquarium, jazz chemistry has transformed them into flugelhorns!

The Amazing Keystone Big Band proves once again that jazz can seize on anything, make every theme its own and turn it into its own carnival, having traveled from Africa to America, from New Orleans to Rio, sweeping Europe off its feet. The diversity of tones – parodic, fairy-tale, lyrical, etc. — of the original score is matched by a wide variety of rhythms and styles, giving the full measure of what a big band is capable of after a century of jazz history. The kangaroos movement thus lends itself wonderfully to an adaptation in style of Harlem stride, inherited from ragtime, where the pianist’s left hand alternates in a fast tempo between basses and chords, adding to the leaps of the right-hand chords written by Saint-Saëns. The hemiones, strange speedy animals from Asia, gallop to the frantic rhythm of unison trumpets, trombones and saxophones in the bebop tradition of Charlie Parker and his colleagues; this new form of virtuoso routine which emerged in the 1940s, is a worthy counterpart to the piano writing of the late 19th century, of which Saint-Saëns was a leading proponent and which he caricatures in this number featuring a wild donkey race. A little later, we leave the United States for Brazil, following the colorful birds of the aviary for a flute samba; for this title, the character-instrument hardly changes – which one better than the flute could mimic the lightness of a bird’s flight? – but the syncopated rhythm amplifies the vertigo effect that characterises Saint-Saëns’ theme.

More than a pretext for arrangement, the music of Carnival of the Animals loses none of its original humor and the principle that presided over its creation: to entertain. Let yourself be carried away by the magic of this Grande fantaisie jazzologique!

Plus qu’un prétexte à l’arrangement, la musique du Carnaval des animaux ne perd rien de son humour originel et du principe qui présidait à sa création : divertir. Laissez-vous donc porter par la magie de cette Great jazzological fantasy!

Manon Fabre